Yojijukugo

Or why you should never fix your shoes in a melon field

In any language, some idioms are simply impossible to comprehend without first knowing the context behind them. While researching ‘yojijukugo’ (四字熟語), a collection of set phrases or idioms in Japanese, I came across this four character expression which is rarely used in contemporary Japan.

‘瓜田李下’ (ka den ri ka)

A literal breakdown of each character could be translated as ‘melon’, ‘field’, ‘plum’, and ‘below’.

Needless to say, the actual meaning of this idiom eluded me. Even after seeing the ancient poem this expression was derived from, I was still very confused. It was only after becoming privy to the full context that I learned to never fix my shoes in a melon field, or adjust my hat under a plum tree.

(Photo by Marco Zuppone on Unsplash)

Modern day Japanese consists of three writing systems, including one derived from Chinese characters called kanji. Yojijukugo are Japanese expressions made up of four kanji characters. In ancient times, Japan was highly influenced by Chinese culture, and four character idioms are one cultural import that made its way over. In Chinese they are called ‘chengyu’, and usually come from ancient literature and historical writings. An important part of these compounds is that they mean much more than the sum of the individual four characters, usually encompassing moral concepts and the wisdom of previous generations.

A chengyu that you probably already know is ‘crouching tiger, hidden dragon’ (臥虎藏龙). This Chinese expression comes from an ancient poem and refers to a place or situation filled with hidden talents or masters.

Many of these Chinese idiomatic expressions were adapted into Japanese pronunciation of the characters, and are still used today. But the tradition was expanded even further on Japanese soil, adding the country’s native proverbs and traditions, as well as incorporating religious texts such as Buddhist scriptures, to create new four character expressions suited to Japanese life. At present, there are thousands of yojijukugo,some are used in everyday speech, while others are more likely to be the preserve of literature and language enthusiasts.

Naturally, yojijukugo are prized for their succinctness. It only takes a few characters to appeal to a historical canon of wisdom and tell a whole story. One example is:

‘晴耕雨読' (sei ko u doku)

‘Fair weather, labour, rain, read’ means to live a quiet but fruitful life, working in the field during temperate conditions and pursuing intellectual endeavours at home when the weather turns unpleasant. In just four kanji, the picture of an idyllic lifestyle has been painted. A Twitter character count would mean nothing anymore if there was a whole language as economical as yojijukugo.

(Photo by Dhafin Kumarajati on Unsplash)

But apart from this obvious benefit, yojijukugo are also particularly poetic. Many have repeated sounds that make the idiom even more pleasing to the ear. A saying that can be often heard is ‘one life, one encounter’:

‘一期一会’ (ichi go ichi e)

Every encounter is once in a lifetime and should be cherished. Something to keep in mind when an annoying, random drunk guy is talking your ear off at a pub.

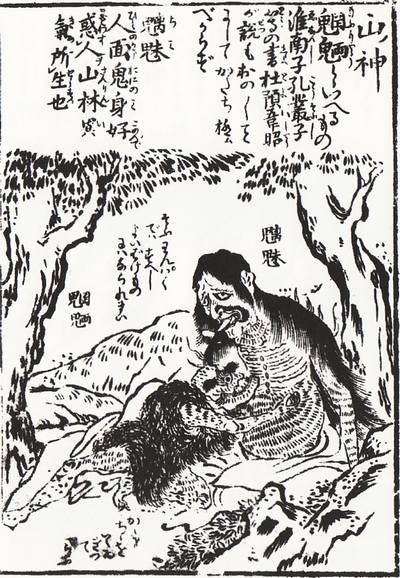

When being devised, all aspects of the four character idioms were taken into consideration. Not only do they sound attractive and express poetic concepts but they look good too. A literary expression taken from Chinese to describe a whole cacophony of evil spirits, demons, and monsters is:

‘魑魅魍魎’ (chi mi mo ryo)

This collection of kanji is visually striking, thanks to the component on the left-hand side that all these complex characters share.

(Source: Edo Iseya Jisuke, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

With so many four-character idioms originating in Chinese classics or Japanese customs, a rare case is:

‘一石二鳥’ (i seki ni cho)

‘One stone, two birds’. As you may have guessed, it is said to derive from the common English saying, ‘to kill two birds with one stone’.

Some ideas are cross-cultural, so there are yojijukugo with meanings that seem to coincidentally line up with existing English idioms. In my opinion, the yojijukugo equivalent of ‘in one ear, out the other’ instills much more arresting imagery.

‘馬耳東風’ (ba ji to fu)

Literally ‘horse ear, east wind’.

(Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

So what does ‘melon field, under the plum trees’ mean? The original Chinese poem that this idiom originates from contains the lines, ‘do not put on shoes in a melon field; do not adjust your hat under a plum tree’. It means don’t do anything to invite suspicion or cause a scandal, however innocent you may be. If you bend down to retie your shoelaces in a melon field, who knows? You could be stealing melons. If you fix your hat under a plum tree, one may think you’re sneaking away with plums hiding under your headwear.

Melon field, under the plum trees.

Basically, keep your head down and stay out of trouble!